Ah, Craig Hinton, the late, great master of continuity porn.

Forever to be remembered as the originator of the word fanwank, a charmingly

enthusiastic presence on the old Continuity Cops mailing group, and as an

author of some of the most enjoyable Doctor

Who fiction of the long wilderness. That was the great thing about Craig:

he loved continuity, live and breathed it, but he still knew how to create a

rollicking good story. Continuity fetishism is usually stifling to creativity,

but Craig had the imagination necessary to avoid this trap.

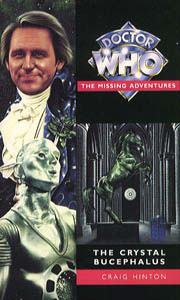

The Crystal Bucephalus

was Craig’s first novel, published in 1994. It doesn’t have the sheer

continuity overload of some of his later works like the sixth Doctor PDA The Quantum Archangel, so it’s a little

more accessible to the more casual fan. But then, how many casual fans were

picking up Virgin’s Missing Adventures line in the mid-nineties? I’m against

continuity in place of creativity, but when it comes attached to a story like

this, it’s the icing on a delicious cake.

The Crystal Bucephalus

was Craig’s first novel, published in 1994. It doesn’t have the sheer

continuity overload of some of his later works like the sixth Doctor PDA The Quantum Archangel, so it’s a little

more accessible to the more casual fan. But then, how many casual fans were

picking up Virgin’s Missing Adventures line in the mid-nineties? I’m against

continuity in place of creativity, but when it comes attached to a story like

this, it’s the icing on a delicious cake.

The Crystal Bucephalus is a time-travelling restaurant built

on an abandoned planet. Shades of The

Restaurant at the End of the Universe in there, of course, with the great,

the good and the rich of the Galaxy meeting to dine at this most exclusive of

locales. However, rather than serving food itself, the Crystal Bucket (as it

has affectionately become known) instead sends it patrons to the greatest

eateries throughout history, where they can interact with the locals, disguised

and unable to alter the flow of time. Which is all well and good, of course,

until things go wrong.

The Doctor, along with Tegan and Turlough, had been happily

enjoying a meal in 18th century France until accidentally being

drawn into the Bucephalus’ time fields due to the presence of two of its

patrons, one of whom is none other than Maximillian Arrestis, the head of the

Elective, the greatest crime syndicate in galactic history and a man of

unparalleled personal vision. His murder raises a few problems, with the Doctor,

as usual, being accused. Two things get him off the hook here: firstly, he owns

the Bucephalus (something he isn’t proud of) and secondly, Arrestis’s murder

doesn’t stick. What follows is an adventure that revolves around the Bucephalus

but impacts on locations throughout time and space.

The novel is based primarily in the eleventh millennium, a period

of history that Craig chose due its being barely explored in the original series.

It’s a period of delicate peace between the remains of the Federation, the

criminal Elective, and the Lazarus Intent, a vast religious organisation that

numbers its followers in the quadrillions. The Intent is at the heart of the events

of the novel, with many decisions revolving around characters’ faith in its

teachings or their abuse of its power. At first, it seems that Craig is

attacking religion, particularly the Christian Church (the Intent is basically

a galactic Holy See), but in time it becomes clear that he is supportive of

faith and the good that organised religion can do, but wary of the harm that it

can be used for if perverted.

That’s not to say this is a deep, philosophical novel. First

and foremost, it’s a soap opera, with much of the drama coming from the

tortured relationships of the Bucephalus’ creator, Alexhendri Lassiter, and his

ex-wives and fellow temporal physicists, Monroe and Matisse. This triangle,

which extends to include Arrestis, is the catalyst for events throughout the tale.

Add to the heartache and backstabbing plenty of violence, murder and temporal

anomalies and you have a cracking, if occasionally contrived, adventure.

Craig nails the central TARDIS trio. His fifth Doctor – who experiences

a lengthy side trip in which he sets up his own restaurant and is adopted by a

furry alien couple in the 63rd century – is particularly well

captured, his grit and resolution coming through despite his recognisable soft exterior.

Tegan’s characterisation strikes the right balance between her frequent

bolshiness and her often forgotten softer side, and she strikes up a strong,

believable friendship with Tornqvist, an important figure within the Lazarus

Intent. Turlough gets less time to shine, but nonetheless hits the right notes

between the self-centred scoundrel he begins as and the slightly less

self-centred near-hero he ends up as. Craig also makes a point of getting the

TARDIS crew out of their uniform-like costumes and into some fancy clothes, although

both Turlough and the Doctor are back in their usual togs by the end of events.

The continuity points are ever-present, but not intrusive. Rather,

they’ll bring a smile to the face of anyone who has followed Doctor Who both on television and during

the early years of the Virgin novel line. The Bucephalus’ time projection is

maintained by Legions, the multidimensional beings that appeared in the New

Adventure Lucifer Rising, while other

species such as the Alpha Centaurians, Chelonians and Silurians appear in

cameos. There are plenty of cheeky hints along the way too; not only is it

insinuated that Turlough’s world of Trion was colonised by the Gallifreyans, it

is also strongly implied that New Alexandria, the planet on which the

Bucephalus is based, is in fact the long-dead corpse of Gallifrey. Then there

are the numerous Star Trek references

for fans to spot, and Lazarus knows what else I’ve missed…

The novel builds to one hell of a

climax, in which the author not only manages to bring the various temporally separated

protagonists together but even finds a decent and believable use for

shapeshifting pseudo-companion Kamelion. Much of the climactic finale takes

place within the belly of the TARDIS, building a far more evocative picture of

the death knells of a timeship than the recent TV episode Journey to the Centre… and even leading into the brand new shiny

console room that debuted in The Five

Doctors.

The Crystal Bucephalus is a grand read for any died-in-the-wool

Who-head. Arguably, Craig Hinton never really managed to craft a story as well

as he did here, often slipping a little too far into the excesses of continuity

fetishism. Nonetheless, I’d love to see what he would made of the mass of

mythology that has built up in the years since his death in 2006. The

marvellous geek.

No comments:

Post a Comment