The first in a series of articles on the animals featured in the Jurassic Park franchise. The JP films are monster movies and not intended to be wholly accurate, but it's fun to look at the real dinosaurs that inspired them and see how they compare.

Appearances: Jurassic Park, The Lost World, Jurassic Park III, Jurassic World

While T. rex is the big draw of the franchise, the Velociraptors are the real stars. Not terribly well known before Jurassic Park, Velociraptor is now one of the most notorious and popular dinosaurs. The word "raptor," originally an old Greek word meaning thief, predator or plunderer, used to be used primarily to refer to birds-of-prey. Nowadays, when someone says "raptor" they're almost invariably referring to Velociraptor or one of its close relatives.

The raptors in the films are particularly exaggerated for dramatic effect. The real Velociraptor was a medium-sized predator, about two metres/seven feet long and half a metre/a foot-and-a-half tall. The raptors in the films are over twice the size of this, standing eye-to-eye with humans. The movie versions are in fact more similar to Deinonychus, a related genus (both are part of the dromaeosaurid family). The Deinonychus was larger, although not quite as large as the JP raptors, and had a deeper muzzle more akin to the movie versions. Part of this is down to when Crichton wrote the original novel; at the time, Deinonychus was considered another species of Velociraptor. The iconic fossil being excavated at the beginning of the story is found in Montana, in the range of Deinonychus fossil sites, while the Velociraptor is only found in Asia. So really, what we're seeing in the JP films is a Deinonychus, not a Velociraptor.

In 1991, another related American genus was discovered: the Utahraptor, an even bigger dromaeosaurid with proportions more similar to the raptors already being developed for the first film. Utahraptor gave the JP raptors a credibility boost and has become one of the most popular dinosaurs itself. Dromaeosaurids are considered some of the most intelligent dinosaurs, characterised by pack behaviour and large brain cases for their body size. However, it's all relative; raptors probably weren't much more intelligent than an average bird species today.

The most significant difference between the real Velociraptor and the JP raptors is in their appearance. When Jurassic Park was being filmed, the appearance of the dinosaurs was, with some dramatic licence, close to contemporary scientific knowledge. Over the following few years, however, a rush of excellently preserved fossils has shown that most coelurosaurian dinosaurs had feathers for warmth and/or display, with some, including the dromaeosaurids, having well developed feathers akin to modern flight feathers. Dr. Alan Grant had to confront a kid whining about the Velociraptor skeleton looking more like a six-foot turkey. He was more right than he knew (and a six-foot turkey sounds pretty terrifying to me). By 2000, the feathered dinosaur was becoming recognised enough that some limited quills were added to the heads of the scaly raptors of JP3, but they've been returned to a fully scaled look for Jurassic World. Part of this is for easier audience recognition, and mostly just because the filmmakers think it looks cooler. There is a handy line in JW covering the discrepancy, though: Dr. Wu points out that all the dinosaurs at the park are hybridised with other species, and that in nature they would "look quite different." Plenty of fans have theorised that the frog DNA used to patch the codes, which was such a major plot point in the first story, made the raptors bald. It would have been a nice touch if, by the time of Jurassic World, they'd started using duck DNA instead because it was a closer match. And it would have stopped them changing sex...

Another myth to be busted: the terrifying image of the Velociraptor slashing open its prey's belly, leaving the guts to flop out. No one is certain, but simulations with sculpted claws and pork bellies make it unlikely that the claw was sharp enough or curved correctly to slice open flesh that way. What seems more likely is that packs of raptors would team up on larger prey, using their sickle claws to pierce the flesh and hang on while they used their razor-sharp teeth to viciously bite at the flesh. The prey would most likely have died of blood loss even if they had managed to shake the raptors off. Much of the time, Velociraptors would have preyed on smaller animals, either around their own size (such as with the famous battling dinosaurs fossil of a Velociraptor and Protoceratops in a clinch), or much smaller, and they would also have scavenged. Not that this makes a pack of raptors any less of a terrifying prospect.

For all the changes made for the books and films, one thing Crichton was dead right on was stressing how bird-like the Velociraptor was. It's clear now that the dromaeosaurids were very closely related to the earliest birds; indeed, some definitions include them as birds (it's very much a matter of semantics). Early dromaeosaurids were tiny animals, extremely bird-like, some of them, such as the abundant Microraptor, with feathers sufficiently adapted for gliding or posibly even powered flight. The sickle claw seems to have initially evolved as a climbing aid for aboreal species, later being becoming weaponised as some branches of the family re-adapted to a terrestrial, predatory lifestyle.

Finally, I'm afraid that the wing-like forelimbs of the Velociraptor mean that it most certainly would not be able to move its hands in such a way to open a secured door.

Appearances: Jurassic Park, The Lost World, Jurassic Park III, Jurassic World

|

| Mounted skeleton of the Velociraptor |

While T. rex is the big draw of the franchise, the Velociraptors are the real stars. Not terribly well known before Jurassic Park, Velociraptor is now one of the most notorious and popular dinosaurs. The word "raptor," originally an old Greek word meaning thief, predator or plunderer, used to be used primarily to refer to birds-of-prey. Nowadays, when someone says "raptor" they're almost invariably referring to Velociraptor or one of its close relatives.

The raptors in the films are particularly exaggerated for dramatic effect. The real Velociraptor was a medium-sized predator, about two metres/seven feet long and half a metre/a foot-and-a-half tall. The raptors in the films are over twice the size of this, standing eye-to-eye with humans. The movie versions are in fact more similar to Deinonychus, a related genus (both are part of the dromaeosaurid family). The Deinonychus was larger, although not quite as large as the JP raptors, and had a deeper muzzle more akin to the movie versions. Part of this is down to when Crichton wrote the original novel; at the time, Deinonychus was considered another species of Velociraptor. The iconic fossil being excavated at the beginning of the story is found in Montana, in the range of Deinonychus fossil sites, while the Velociraptor is only found in Asia. So really, what we're seeing in the JP films is a Deinonychus, not a Velociraptor.

|

| The somewhat amended JP3 raptor. |

The most significant difference between the real Velociraptor and the JP raptors is in their appearance. When Jurassic Park was being filmed, the appearance of the dinosaurs was, with some dramatic licence, close to contemporary scientific knowledge. Over the following few years, however, a rush of excellently preserved fossils has shown that most coelurosaurian dinosaurs had feathers for warmth and/or display, with some, including the dromaeosaurids, having well developed feathers akin to modern flight feathers. Dr. Alan Grant had to confront a kid whining about the Velociraptor skeleton looking more like a six-foot turkey. He was more right than he knew (and a six-foot turkey sounds pretty terrifying to me). By 2000, the feathered dinosaur was becoming recognised enough that some limited quills were added to the heads of the scaly raptors of JP3, but they've been returned to a fully scaled look for Jurassic World. Part of this is for easier audience recognition, and mostly just because the filmmakers think it looks cooler. There is a handy line in JW covering the discrepancy, though: Dr. Wu points out that all the dinosaurs at the park are hybridised with other species, and that in nature they would "look quite different." Plenty of fans have theorised that the frog DNA used to patch the codes, which was such a major plot point in the first story, made the raptors bald. It would have been a nice touch if, by the time of Jurassic World, they'd started using duck DNA instead because it was a closer match. And it would have stopped them changing sex...

Another myth to be busted: the terrifying image of the Velociraptor slashing open its prey's belly, leaving the guts to flop out. No one is certain, but simulations with sculpted claws and pork bellies make it unlikely that the claw was sharp enough or curved correctly to slice open flesh that way. What seems more likely is that packs of raptors would team up on larger prey, using their sickle claws to pierce the flesh and hang on while they used their razor-sharp teeth to viciously bite at the flesh. The prey would most likely have died of blood loss even if they had managed to shake the raptors off. Much of the time, Velociraptors would have preyed on smaller animals, either around their own size (such as with the famous battling dinosaurs fossil of a Velociraptor and Protoceratops in a clinch), or much smaller, and they would also have scavenged. Not that this makes a pack of raptors any less of a terrifying prospect.

|

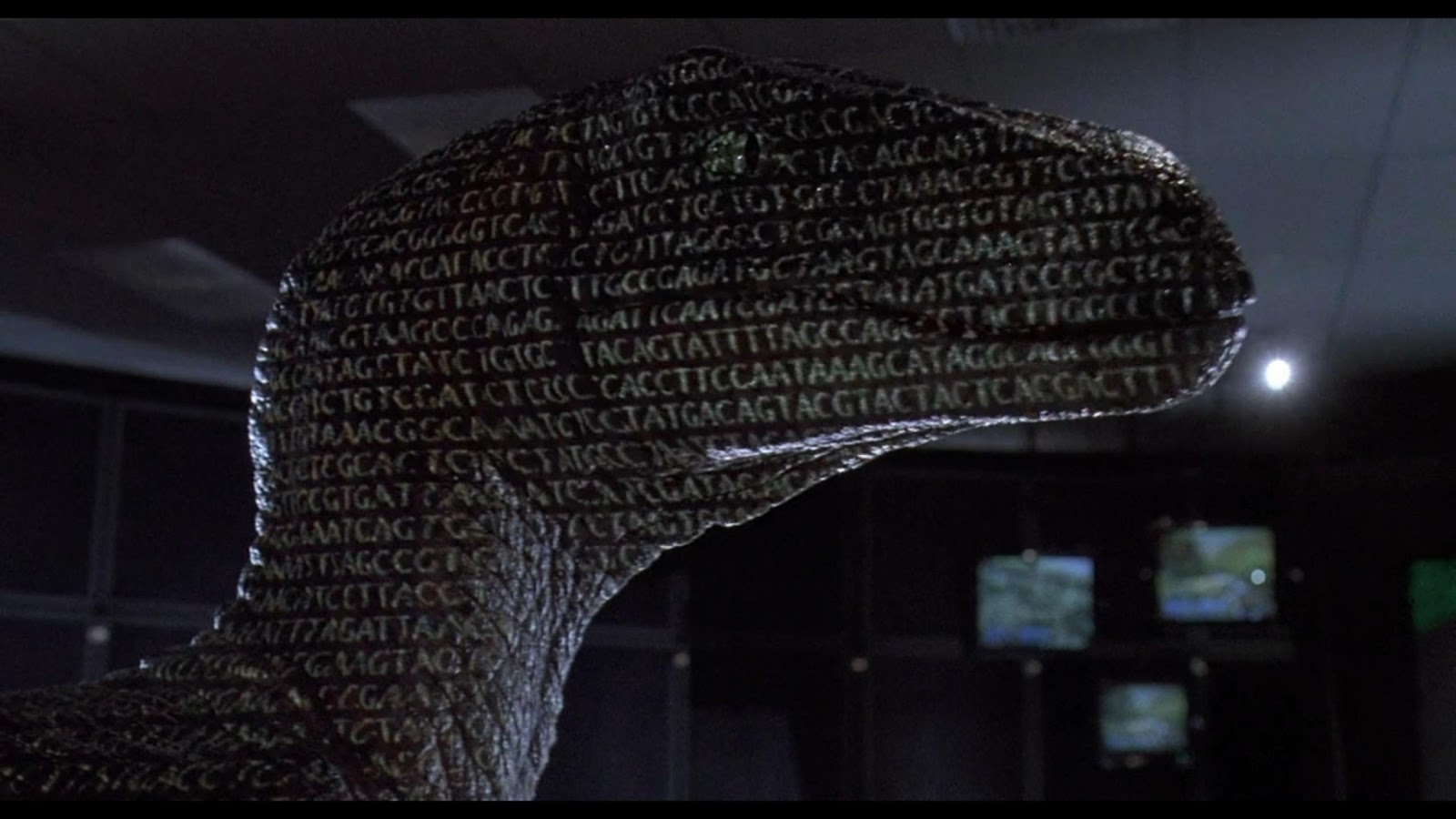

| A classic shot from the first JP |

For all the changes made for the books and films, one thing Crichton was dead right on was stressing how bird-like the Velociraptor was. It's clear now that the dromaeosaurids were very closely related to the earliest birds; indeed, some definitions include them as birds (it's very much a matter of semantics). Early dromaeosaurids were tiny animals, extremely bird-like, some of them, such as the abundant Microraptor, with feathers sufficiently adapted for gliding or posibly even powered flight. The sickle claw seems to have initially evolved as a climbing aid for aboreal species, later being becoming weaponised as some branches of the family re-adapted to a terrestrial, predatory lifestyle.

Finally, I'm afraid that the wing-like forelimbs of the Velociraptor mean that it most certainly would not be able to move its hands in such a way to open a secured door.

No comments:

Post a Comment